WASHINGTON-The U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation Thursday that would remove gray wolves from the federal Endangered Species List. If passed by the Senate, it will return primary management authority to the states. A change that would not affect Arizona’s Mexican gray wolves, which are listed separately under federal law.

The measure, H.R. 845, known as the Pet and Livestock Protection Act, is sponsored by Rep. Lauren Boebert (R-Colo.). The bill passed the House by a 211–204 vote, largely along party lines, and now heads to the U.S. Senate for consideration.

If enacted, the legislation would reinstate a 2020 rule issued by the U.S. Department of the Interior that removed gray wolves from protections under the Endangered Species Act. That rule was overturned in 2022 by a federal judge, restoring federal protections across much of the country.

Supporters of the bill argue that gray wolf populations have long since recovered and that continued federal oversight has limited states’ ability to manage wildlife and address conflicts between wolves, livestock producers, and rural communities.

Opponents say federal protections remain necessary to prevent population declines and ensure long-term recovery across the species’ range.

What the bill would do.

The Pet and Livestock Protection Act directs the Secretary of the Interior to reissue the 2020 delisting rule. It prohibits judicial review of that decision, preventing future lawsuits challenging the removal of gray wolves from the endangered species list.

Under the bill, responsibility for managing gray wolf populations would essentially shift to state wildlife agencies. States would be responsible for setting population goals, responding to livestock depredation, and determining whether to allow hunting or trapping seasons.

The legislation does not establish new federal recovery benchmarks or management standards; instead, it relies on states to regulate wolves under their own laws once federal protections are removed.

Arizona’s situation is different.

While the bill would significantly affect wolf management in parts of the Northern Rockies and Great Lakes regions, its immediate impact in Arizona would be limited.

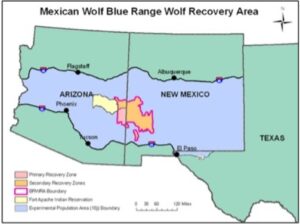

Nearly all wolves in Arizona are Mexican gray wolves (Canis lupus baileyi), a distinct subspecies of the gray wolf (Canis lupus) that remains separately listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Mexican gray wolves were reintroduced into eastern Arizona and western New Mexico in 1998 as part of a federal recovery program after being nearly eliminated from the wild in the United States.

Because H.R. 845 focuses on the broader gray wolf listing and reinstates a rule that did not delist Mexican gray wolves, the Arizona Game and Fish Department would not automatically assume full management authority if the bill becomes law.

Instead, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would remain the lead agency overseeing Mexican gray wolf recovery in Arizona, with Arizona Game and Fish continuing to serve as a cooperating agency. The state assists with population monitoring, livestock depredation investigations, and coordination with ranchers, but does not set independent population targets or authorize hunting seasons.

How Mexican gray wolves differ from gray wolves.

Mexican gray wolves differ from other gray wolves both biologically and geographically.

They are the smallest subspecies of gray wolf in North America, typically darker in color with black, brown, and rust-colored markings. Historically, Mexican gray wolves occupied parts of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico, including Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

Unlike gray wolves in the Northern Rockies and Great Lakes regions — where populations rebounded more quickly — Mexican gray wolves were almost entirely eradicated by the mid-20th century. The current population descends from a small number of wolves captured and bred in captivity, resulting in ongoing concerns about genetic diversity.

Federal wildlife officials have cited the subspecies’ limited range, smaller population size, and genetic constraints as reasons for maintaining ESA protections, even as gray wolves elsewhere have exceeded recovery goals.

-

Occasionally, individual “northern” gray wolves (Canis lupus) — typically dispersing animals from Utah, Colorado, or the Northern Rockies — may pass through or briefly enter northern Arizona.

-

These occurrences are rare, temporary, and involve single animals rather than established packs.

-

Arizona does not have a resident breeding population of non-Mexican gray wolves.

Mexican gray wolf population numbers in Arizona.

According to the most recent annual survey by state and federal wildlife agencies, at least 286 Mexican gray wolves were living in the wild across Arizona and New Mexico at the end of 2024. Of those, approximately 124 wolves were counted in Arizona, primarily in Apache and Greenlee counties.

While the population has increased steadily over the past decade, it remains geographically concentrated, another factor contributing to continued federal oversight.

Mexican gray wolves are considered the most endangered subspecies of gray wolf in North America.

A long history of federal management.

Gray wolves were first listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1974, placing their management under federal control. Since then, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has overseen recovery efforts, including habitat protections, population monitoring, and reintroduction programs.

Over the years, the federal government has attempted multiple times to delist wolves or return management authority to the states. In some regions, Congress or the Interior Department has successfully shifted management to state agencies. In other cases, federal courts have overturned delisting efforts, citing procedural or scientific shortcomings.

The 2020 delisting rule referenced in H.R. 845 was one such attempt, with a federal judge ruling that the Interior Department failed to consider impacts on wolves in portions of their range adequately.

Supporters and critics weigh in.

Supporters of the bill say states are better equipped to manage wildlife and respond to conflicts, particularly in rural areas where livestock losses have fueled opposition to continued federal protections.

Critics argue that removing protections through legislation bypasses the Endangered Species Act’s science-based process and could lead to aggressive management policies that reduce wolf populations below sustainable levels in some states.

What comes next?

The bill now moves to the U.S. Senate, where similar wolf-related legislation has stalled in the past. If approved by the Senate and signed into law, the measure would represent one of the most significant shifts in federal wildlife policy in decades.

Even if enacted, Mexican gray wolves in Arizona would remain federally protected unless Congress or the Interior Department separately acts to change their status under the Endangered Species Act.

For now, wolf management in Arizona will continue under the existing federal recovery program, with Arizona Game and Fish maintaining a supporting role alongside the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Mexican gray wolves are federally protected under the ESA as an endangered subspecies with a specific recovery and management program. Those protections are separate from the general gray wolf protections addressed by bills like H.R. 845, and they remain in effect unless and until Congress or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service takes separate action to change their status.